| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| Download It (13.52 MB) | 13.52 MB |

If the focus on Africa issues and challenges is well established, there is one variable in the root causes that did not receive the proper attention from the international and regional organizations dealing with peace and security and related matters: separatism.

Indeed, separatism and secession have so far been mainly the focus of scholars, Groups studies and alike. There is no agenda item dedicated to separatism in any United Nations or regional organizations forums, while an overwhelming amount of thematic issues related to Africa are discussed in New-York, Geneva, Brussels, Addis Ababa and elsewhere.

What is interesting in the way separatism has been approached is a case study from a North Versus South perspective.

The North has so far rejected separatism in its sphere and favoured compromise solutions to ethnic, linguistic, cultural groups by championing forms of power sharing such Autonomy regimes for Greenland, Aland Island, Faeroe, Madeira and Azores as well as decentralized and empowered regions, to name a few.

The rejection by European countries of secession of Crimea from Ukraine, emphasizes Europe resolve to reject separatism. Thus, denying the misuse of self-determination and referendum as was the case of Crimea.

Another example of dismissal of separatism in Europe is Catalonia attempts to break away from Spain. Not even the vote by its people, compelled European institutions or its grass roots movements, especially in the Nordic countries (usually eager to embrace secessionists groups in Africa, Latin America or Asia)to wildly espouse the Catalan wish to break away from Spain.

One would wonder how the same countries would react to a similar scenario in Africa ?

In Africa, European and North American NGO’s and influence groups with different agendas have enthusiastically embraced causes of false claims of self-determination to what they perceive as the weak party in most of the intra-states and inter-states conflicts. They would be sympathetic to claims of self-determination rather than claims of state sovereignty and territorial integrity, fuelling intractable conflicts on the peace and security agenda of the United Nations.

In attempts to understand the present and to foresee the future, it is of paramount importance to look at the past and the dynamics since the end of colonialism in Africa:

Since the early years of independence to nowadays, separatism was a constant threat to African States’ sovereignty and territorial integrity. No African State is immune from separatism or secession. The early Pan African leaders of the continent were all too aware of the vulnerability of the continent to secession.

In 1961, at the invitation of King Mohammed V, in the Moroccan port city of Casablanca, the aspirations of Africa leaders were shaped in the what we refer to as Casablanca Group. The conference brought together some of the continent’s most prominent statesmen like Dr. Kwame N’Krumah, Modibo Keita, Gamal Abdelnasser and Sekou Touré. They developed an ambitious agenda for continental integration in the Casablanca Charter that inspired many continental policies and fostered African Unity. The artificial delimitation of borders by the colonizers left a cross-border distribution of ethnic groups and has fostered in many instances the disintegration of states or imposed on States to live with a constant separatist threat for decades.

Historians and scholars in general agree that if Africa managed to turn the page of Decolonization, it is still facing the predominance of conflicts and zones of tensions, testimony of the vulnerability of Africa and the weakness of its national and regional institutions.

In some conflicts, how States dealt with their colonial legacy after independence also plays a role in the emergence of separatist movements.

Separatism and secession go back a long way in Africa. They have both emerged during the early days of independence of African States. The examples of the attempts of secession of Katanga in the Democratic Republic of Congo and of Biafra in Nigeria, are the most famous ones and were contained successfully with foreign interventions.

Separatism in Africa continue after decades of independence to be a reality of the present moment. Across the five regions of the continent (North Africa, West Africa, Central Africa, the Horn of Africa and Southern Africa), separatist movements are active and represent a threat to national, regional and continental security. Today, the vast majority of African States are confronted indiscriminately with separatism under different forms.

Contemporary examples of secession and its outcomes in Africa raise serious questions and doubts about the outcomes of breakaway states as indicated in the introduction of this paper. The general approach to calls for secession in Africa, as set out by the African Union (AU) and its predecessor the Organization of African Unity, is that they should be opposed. The most frequently heard argument against secession is that granting the right to one country invites others to take the same step.

Recent examples suggest that separation isn’t always the best option for impoverished and struggling regions and countries. The division has led to violent border disputes, economic complications, and poor relations with the wider international community that continue nowadays, unabated.

There is also a case to be made that granting secession has merely served to fuel the claims of other separatist movements. Any secession involves the recognition of an accepted border between the two states involved. In many cases, this has proved contentious, with continuous territorial disputes between the states involved, at the expense of regional peace and security.

The continuing border disputes have resulted in the parties to such disputes continuing to invest heavily in their armies and in equipment. They maintain large and costly forces facing each other across their disputed border. Mutual suspicion and accusations of incursions by both armies persist.

This, the argument goes, would put at risk the internationally recognized system of post-colonial states in Africa. The issue of secession first arose in the 1960s with the first wave of decolonization and questions over the viability of the newly independent states across the continent. Two cases stood out: the Congo, where Katanga’s self-proclaimed breakaway was defeated by United Nations forces; and Nigeria, where the Biafran secession was ended by the Nigerian federal forces.

Overall, the borders inherited from colonial powers constitute a fertile ground for separatism, instability and secession scenarios. Societies were torn apart without taking into account the history and traditions of the African people. The kingdom of Kongo, for instance, run from Angola to the southernmost part of Gabon, comprising present northern Angola, a big portion of the Democratic Republic of Congo, the republic of Congo and Gabon. The capital of the kingdom of Congo is Mbanza-Kongo, in today Zaire province in Angola.

In sub-Saharan countries, there are still hotbeds of attempts of secessions with different levels of recurrence and instability. The secessionist movement of Caprivi from Lozi people continue to be a headache for Namibia that reject its claim to independence, while actively supporting a similar claim from the “Polisario front” in North Africa.

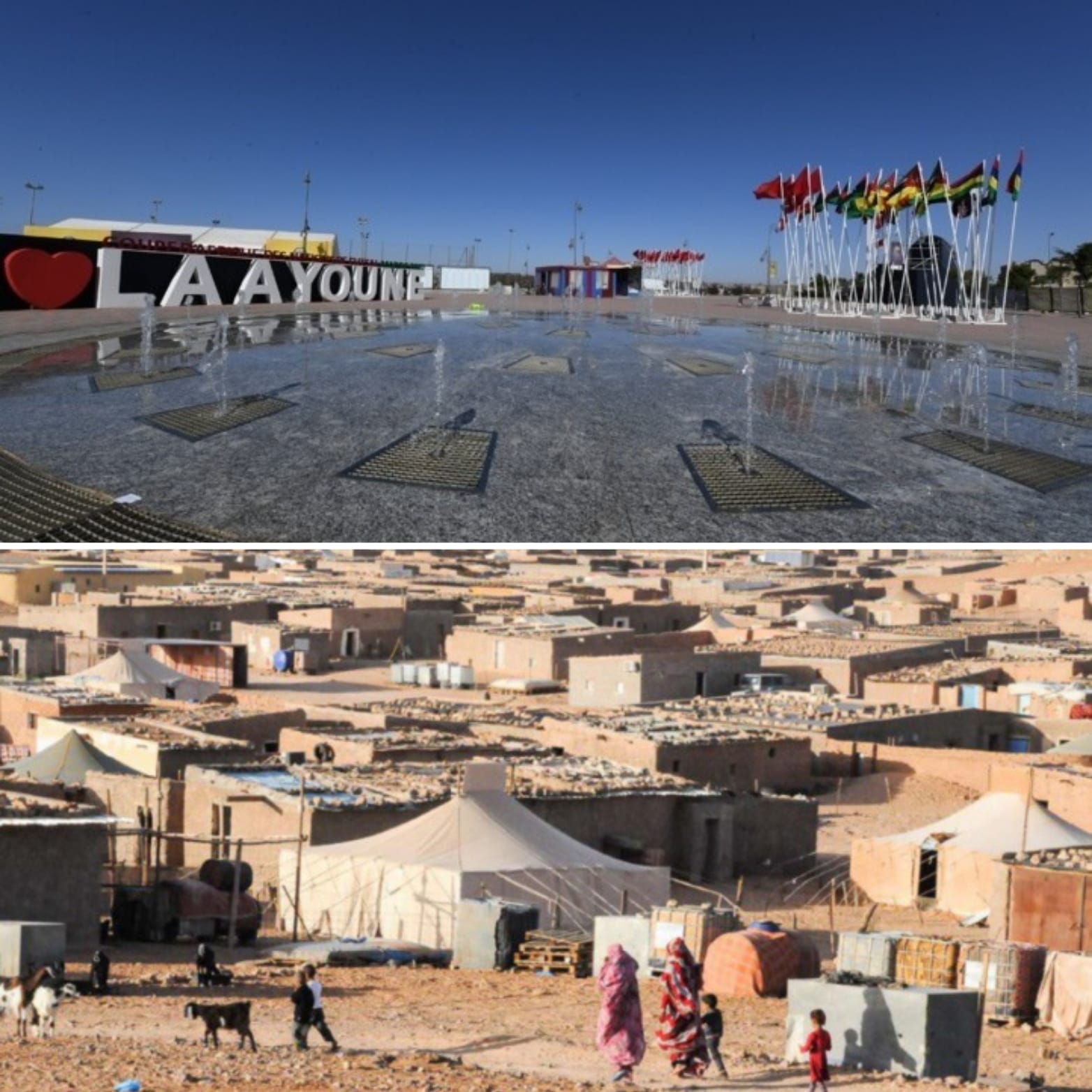

This case is greatly demonstrated through the Regional dispute over “western Sahara”, where the separatist group “Polisario” has for close to half-century with the active support of Algeria attempted to divide Morocco’s territory by half, while historic and legal evidence points out to the continuity of the population of the Sahara throughout southern Morocco that bear the same religious, linguistic and cultural characteristics as the other parts of Morocco.

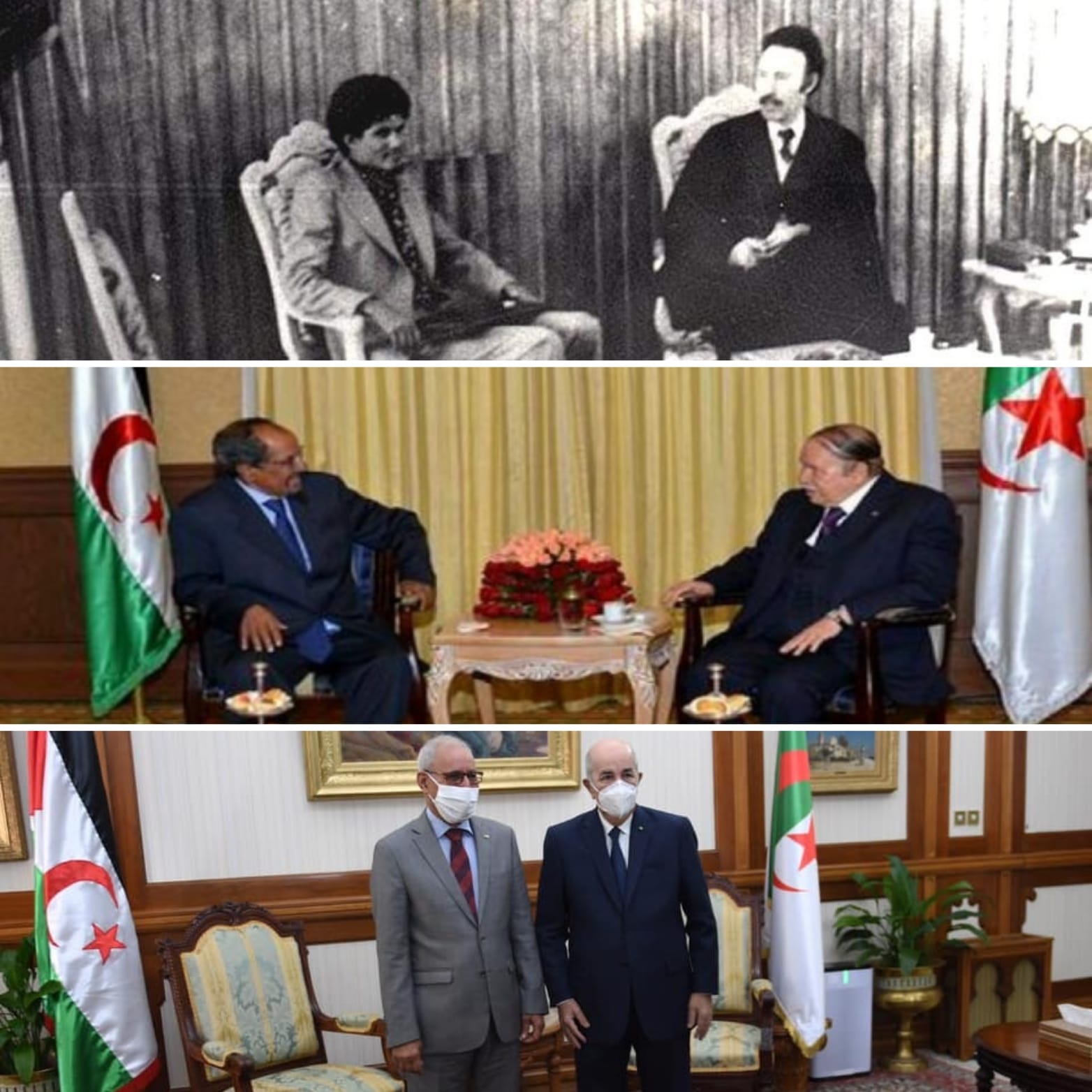

In 1976 and while Morocco was amid its negotiations with Spain for the process of decolonization of the remaining part of the Sahara, which it claimed since 1957 in the UN, few months after the Kingdom’s independence and one month after its membership in the UN, Algeria pushed “Polisario” members to declare the creation of the so-callad “Sahrawi arab democratic republic” in the Tindouf Camps, in the Southwestern part of its territory.

Ever since, Algeria has played an active and defining role in the regional dispute of “Western Sahara”. It has conducted a proxy-war through “Polisario” with Morocco during close to half a century. Since then, “Polisario” carries a secessionist agenda which benefits from the total and multidimensional support of Algeria (diplomatic, logistic, military, financial). Algeria’s role as a full-fledged party in the regional dispute is well known to academics, analysts and political leaders. Yet, for the ordinary citizen, it is an unknown because Algeria has always hid its true role and tried to divest it by pretending to be a “neighbour”, “an interested party”, or “an observer”.

Algeria and “Polisario’s” failure to impose the separatist agenda is due to many factors. First and foremost, the bulk of the United Nations membership don’t recognize the so-called “sadr”. “Polisario” itself is undermined by intestine fights. Many influential “Polisario” members and breakaways groups (Khat Achahid, Sahrawi Initiative for Change, Sahrawis for Peace…) have lost faith in “Polisario” and have preferred to regain their motherland Morocco. On the other hand, Moroccan Sahrawis have the highest political participation in elections held in the Kingdom. A new generation of Morocccan Sahrawis leaders have emerged from the ballots as democratically elected representatives and manage their regional Affairs. The conjunction of these parameters pushed “Polisario” on the edge and allowed the emergence of new activities like smuggling, foreigners kidnapping, international aid embezzlement, drug and small arms illicit trafficking as well activities of terrorism and extremism.

“Polisario’s” involvement in illegal activities of different types of trafficking has been under great scrutiny from International Organizations. Furthermore, many “Polisario” members found to be active in transnational criminal networks and were arrested for acts related to human trafficking and the trafficking of arms, automobile spare parts, cigarettes. The vulnerability of the cooperation for border security between Maghreb countries and the lack of cooperation between the AMU members has facilitated an increased role played by “Polisario” members in the spread of all kinds of illicit trafficking.

The Sahel region, known for its great vulnerability, has become in the last two decades an area of drug transit area between Latin America and Europe. “Polisario” has invested its members in an illicit drug traffic between Latin America and both of Europe and the Gulf region. In 2007, a network of narcotics trafficking was dismantled in the North of Mauritania. It was revealed that some elements of the “Polisario” used the locality of Fdirik, twenty kilometres from Zouerate in Northern Mauritania as a platform for drug export to the aforementioned regions.

“Polisario” has its headquarters in the camps of Tindouf of Algeria which represents a strategic area for arms and drugs smuggling and an ideal point of passage between the Eastern Sahel and the Western Sahel. In 2010, a “Polisario” member was arrested in Smara in the Moroccan Sahara for arms trafficking. He had connections with Mauritania, Northern Mali and was known to be one of the most active arms smugglers in the triangle Mauritania, Mali and Algeria.

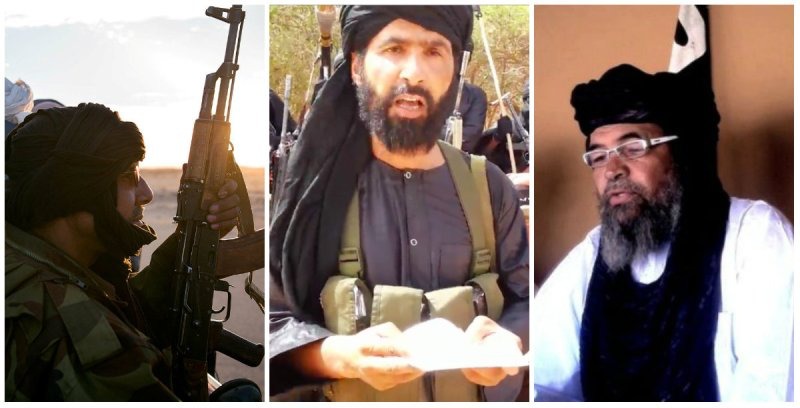

Besides criminality, the “Polisario” has collusions with Al Qaeda in the Maghreb (AQIM). Since its first days of creation in 2007, the growth of Islamism and radicalism emerged in Algeria and and started tightening its relations with “Polisario” for terrorist and smuggling services between the Maghreb region and the Sahel. The collusion of “Polisario” and AQIM was confirmed between 2005 and 2007 when a group of “Polisario” members were caught in terrorist missions with Al Qaeda at the borders of Mauritania.

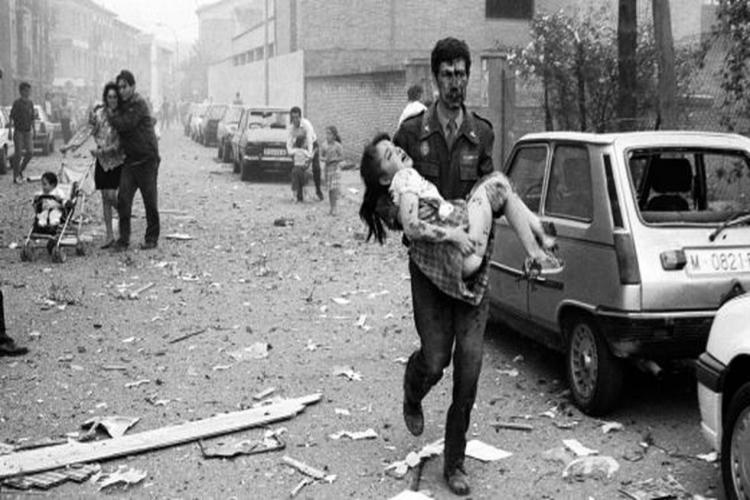

The rise in terrorism and violent extremism in Africa has created severe security threats as this growing phenomenon has resulted in death, destruction and instability in the countries and regions where terrorist groups operate. Social, political and economic factors can be attributed to the causes of this threat. In Nigeria, the actions of Boko Haram have left thousands of people dead and displaced. It has also made neighbouring countries susceptible to bombings and kidnappings. The same can also be said for Somalia, where al-Shabaab threatens to destabilise an already fragile state, impeding sustainable development and democracy. Whilst these and other groups are prevalent in the north, east, west and Horn of Africa, they have created a continental dilemma as they threaten the larger African political, social and economic security.

The spread of extremist and terrorist activities in Africa results out of the existence of countries that are affected by armed conflicts experience fragile security situations, bad governance, organized crimes, social and economic inequalities, and political instability. Extremism rises as a result of intractable conflicts, separatism, violent and dispersed non-state armed groups, with many of them using weapons and armed fighters. [1] These categories even in some occasions, infiltrate political parties and create out of them new terrorist groups, making a conflict more complex to resolve. Between 1989 and 2014, more than 88% of all terrorist attacks occurred in countries experiencing or involved in an ongoing conflict.

This figure demonstrates inherent links between conflict and violent extremism. Nowadays, extremist Islamic movements are prevalent in Northern Nigeria, Niger, Cameroon, Mali, and Chad, carrying out cross-border attacks assisted by open and porous borders and movement of illegal immigrants.

The activities of radical Islamist movements such as Boko Haram in North-Eastern Nigeria and Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) in Mali continue to constitute threats to national and transnational security. In the West African sub-region, Nigeria, Mali, Niger, and Chad are countries that are currently experiencing increasing activities of radical Islamist movements with an estimated population of over 140 million Muslims.[1]

Preventing the flow of illicit arms circulating on the continent and towards conflict zones is one of the key pillars of AU’s initiative “Silencing the guns 2020”. Yet some 2.5 million people with more than 7million facing starvation, degradation of infrastructure, and over 37,530 deaths over a seven- year period (2011-2018)[1] and has resulted in transnational insecurity with consequences for humanitarian, economic, and diplomatic stability in north eastern Nigeria, Chad, Niger, Cameroon and Mozambique recently. The insurgency in Cabo Delgado province in Mozambique, mainly fought by Islamist militants trying to impose an Islamic state in the gas rich region, forcing the French company “Total” to halt its gigantic project that would have made Mozambique a leading gas exporter.

The African Union has put forward so many ambitious agendas to reverse the dynamics of failures and to envision a brighter future for its people. From mechanisms for mediation in conflicts to economic and development programmes and so on. But secession and separatism continue to be absent from Addis discussions and decisions.

The simmering calls for secession from differents groups in all parts of Africa would, one day, be the wakeup call for Africa to address the issue. Africa would not only comprise 54 States but one hundred or two hundred States which would result in an unmanageable continent and would kill any serious attempt of integration. The implementation of the recomposition of colonial borders would also open the door to the dislocation of all African States, to civil war and to endless internal conflicts manipulated by external States and the great powers in search of land and raw materials.

Separatism will cost Africa its path to development, progress and prosperity. Africa, instead of transforming itself and once again becoming a vast space open to the circulation and exchange of people, ideas and goods, with the break-up of existing states, is moving towards the creation of unnamed micro-states , speechless, without weight.

Despite the relative decline of the nation-state in a world which today is that of supranationality, of large transnational economic and political groupings, it is nevertheless necessary to undertake, urgently, from now on, the construction of Nation-states in the continent to include the region in the new supranational restructuring of the globe at the risk of a regression of this portion of the continent in partitions and in infra-nationality.

The time has come to build a real African agenda for the twenty-first century in the face, indeed, of the risks of state dislocation, when we should move forward towards building large unified African spaces which would be the continent's own strength. It is important that, on the continental level, to have a vision of where Africa stands vis-à-vis the great powers. The Vision of the Founding Fathers of Africa in the Casablanca Conference, 60 years ago is the way forward for African unity. Separatism can’t strive if “Africa trusts Africa” and neighbors cooperate genuinely instead of undermining each other’s territorial integrity.

One cannot fight separatism at home and promote it at the door´s step of its neighbors, remain a fundamental principle.

Grace Njapau and Evaristo Julio Gomes