| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| Download "The War on Terror from the Sahara to the Sahel" (6.86 MB) | 6.86 MB |

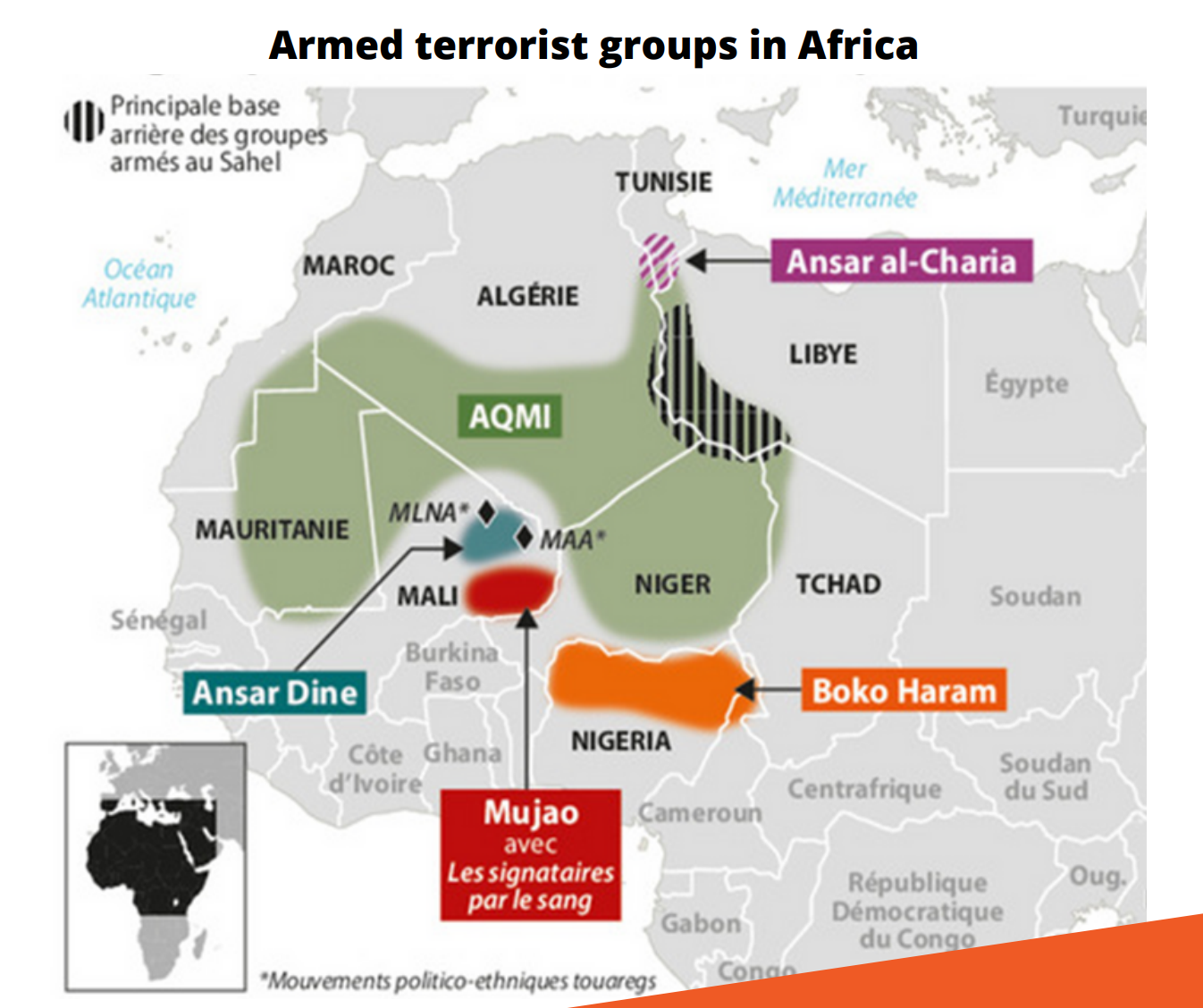

It is most often customary to limit geographically and chronologically the ongoing fight against terrorism, in the context of the anchoring of jihadist terrorism, to the Western part of the African continent, starting from the 2010-2020 decade.

This is how the war against terrorism in the Sahel-Saharan strip, waged against the followers of Al Qaeda and Daesh, is defined. Yet, the junction between terrorism on the shores of the Mediterranean, the Sahara and the Sahel, seems somewhat insufficiently deciphered.

The proliferation and abundance of arms from the international trafficking of Small Arms and Light Weapons (SALW) in the Sahel and Sahara region is a reality that has been widely exploited by several armed groups, including the “Polisario”.

Several members of the militia, with the tacit support of Algiers, have joined the armed terrorist groups that abound in this area. The International Convention against the Recruitment, Use, Financing and Training of Mercenaries by the United Nations fully applies to this phenomenon, of which Morocco has been the target since the creation of the “Polisario” in 1973.

Criminalisation refers to the multiplication of acts contrary to legality. Several events that have taken place are enough to qualify this entity with this term. The blockade in the Guerguerate border crossing between Morocco and Mauritania last November showed that Algeria's military agenda seems to be gaining momentum, through, among other tools of warfare, a particularly offensive informational and hybrid war, via the Algerian Press Service (APS) agency (the official Algerian press agency).

On the other hand, the Brahim Ghali case will have demonstrated, once again, Algiers' destabilising agenda towards its neighbours, putting two essential partners at odds with each other: Spain and Morocco. It is well known that the “Polisario” leader entered Spain with an Algerian identity and diplomatic passport, on board an Algerian presidential plane. Brahim Ghali has been, however, the subject of an international arrest warrant issued by the Spanish judiciary through its highest court, the Audencia Nacional, since November 2016 a few months only after becoming the head “Polisario” for crimes against humanity, including his involvement in the death of nearly 160 people between 1980 and 1990[1].

- Sahara, Sahel: common security challenges and realities in the fight against armed terrorist groups…

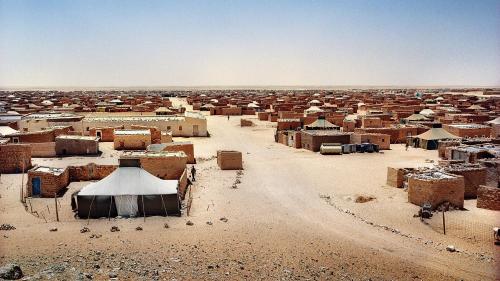

For the past ten years, the Tindouf camps have been a fertile breeding ground for terrorist movements in the Sahara's periphery: the Sahel.

De facto, it is in the Sahara, where the “Polisario” has been trying to operate since its creation by Algeria and the Kadhafi regime in April 1973, that the geographical and sociological interconnection between the Sahel and the Sahara should be analysed more closely than it currently is.

We know, of course, the lineage of the man who presents himself as the “Emir” of the “Islamic State in the Great Sahara” (EIGS), Adnane Abou Walid al-Sahraoui. The latter, who first experienced with terrorism within the armed wing of “Polisario”, pledged allegiance to “ISIL” in May 2015.

Since then, his brother - number 2 of the terrorist organization, Abdel Hakim al-Sahraoui, who died in Mali in Menaka at the end of May - and he, both born in Laayoune - have spread terror and desolation in the region falling between Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger. At the beginning of 2021, the UN recalled that 4,250 Malians, Nigeriens and Burkinabés were victims of terrorism during the year 2020. The terrorist organization and Adnane Abou Walid al-Sahraoui are thus involved to the latest attack that bled the locality of Solhan, located in the North of Burkina Faso, and caused the death of 160 people during the night of 4 to 5 June.

The multiple attacks carried out by this terrorist movement, whose links with the “Polisario” are undeniable, show the degree of danger it poses to the entire region.

This complicity between the “Polisario” and terrorist organisations has been demonstrated by the investigations carried out by the Moroccan anti-terrorist services and the successive dismantling of terrorist cells. This reality attests to the crisis that the separatist movement is going through.

Most of the former combatants have left and turned to business in Mauritania. Many historical leaders have also left, as well as younger members, although there are still a few youngsters within the group. This entails harmful effects for at least two groups:

- First, maintaining the same radical political line while the position of the Moroccan adversary has evolved, thus taking hostage the tens of thousands of Saharawis living in the Tindouf camps.

- Secondly, by refusing to engage in dialogue, the “Polisario” has no choice to radicalise its message, making more and more frequent allusions over the last two years to a possible resumption of armed struggle. These allusions became explicit during the last “Polisario” "congress" held in Tifariti in 2019. Their theatre of operation is the buffer zone, legally under Moroccan sovereignty and placed under the responsibility of the UN, as evidenced by Resolution 2548, voted by the UN Security Council on 30 October 2020, opening an inclusive dialogue on the Sahara issue.

It is obvious that among those who are sensitive to it, this war dialectic leads to believe that only violence can bring what has been promised to them, while it is obvious to most observers that the Sahara issue will only be resolved through dialogue and compromise.

By playing on this "military" message, the “Polisario” leaders artificially maintain radicalisation among the populations of the camps, pushing some of them, especially among the youth, to Islamist terrorism.

- A Sahelian terrorism that has its roots in the one that struck Morocco:

One must not, however, overlook nor forget the first attacks that affected the African continent, following the example of those that have hit Morocco hard over the last twenty years.

This reality, which is somewhat downplayed, unfortunately confirms the survey carried out by the Foundation for Political Innovation: "Islamist attacks in the world between 1979 and 2019", which states that 91.2% of the victims of Islamist attacks come from Muslim countries (compared to 0.9% for Europe) with 44.3% of them coming from the North African and Middle Eastern regions.

First, almost 27 years ago, there was the attack on the Atlas Asni Hotel in Marrakech on 24 August 1994, which cost the lives of two Spanish tourists. Without doubt, this was a certain form of externalisation of the violence that plagued neighbouring Algeria during the black decade (1991-2002).

Then, on 16 May 2003, there were the five attacks that hit Casablanca, in what seemed to constitute a “pattern” for the upcoming ones taking place on the European continent during the following decade.

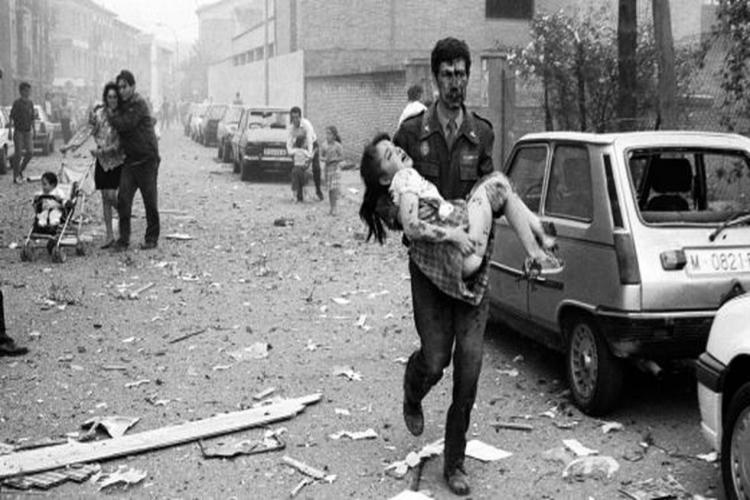

This was the case, unfortunately, shortly afterwards, on 11 March 2004 in Madrid, and then on 7 July 2005 in London. Ten years later, it was the turn of Paris to be heavily mourned, on 7, 8 and 9 January and on 13 November 2015, resulting in the deaths of 159 of the 317 people killed in Islamist attacks since 1979.

Virtually, all the “ingredients” of the terrorist chaos that has become “entrenched” in Europe, sub-Saharan Africa - more precisely in the Sahel - and the Middle East were already present in Morocco, through these early stages of hyper-terrorism.

Like those that targeted the Bataclan, several Parisian café terraces and the Stade de France on 13 November 2015; the Splendid Hotel and the Cappuccino café in Ouagadougou in January 2016; or the Radisson Blu hotel in November 2015 and the La Terrasse restaurant in Bamako in April 2015; the places targeted in Casablanca by the Islamist terrorists were also "symbolic" (a hotel and a restaurant very frequented by foreign tourists; a Jewish cemetery as well as the building that housed the Alliance Israelite, the Belgian Consulate... ).

The choice of targets mentioned above, the methods used (suicide attacks coupled with bombs placed in symbolic places), the sociology of the terrorists and the phenomenon of localised radicalisation (in this case in the Sidi Moumen district) are not without reminding us of the very strong symbolic charge of the attack that targeted the Argana café on 28 April 2011, on the Place Jemaa-El-Fna, in Marrakech.

In short, Morocco enjoys, somewhat in spite of itself, a certain pre-eminence of the terrorist threat and de facto a certain form of legitimacy in its security response, at the cost of many victims on its own territory.

Over the course of some 350 different operations fomented against Morocco and 175 terrorist cells dismantled since 2002 by the various dedicated services, responsible for punishing offences under Article 108 of the Moroccan Penal Code (banditry in all its aspects: the fight against the circulation of weapons/explosives, drug trafficking, attacks on state security, forgery of money and documents) Morocco has acquired a dearly maturity when facing these situations.

This security network has enabled the thwarting of numerous planned attacks and kidnappings, as well as putting the brakes on the junction between actions linked to organised crime, armed groups and terrorist organisations, and the criminal projects envisaged by some 1,500 Moroccans who have left to join Daesh in Iraq and Syria, 600 of whom died on the spot...).

Last March, the Spanish police arrested a radicalised “Polisario” activist who was planning to commit terrorist acts against Moroccan institutions in Spain and abroad. This shows how separatist activism on European soil still represents a threat for the North African region as well as for Europe.

To limit the conflict to the western part of the Sahel-Saharan strip - a vast area of 5 million km2 , stretching from Mauritania to Sudan, with Mali, Niger, Chad and Burkina Faso at its epicentre, to which can be added southern Libya, north-eastern and north-western Nigeria and Cameroon - does not accurately reflect the complexity and interconnection of the agendas shared by the countries bordering the Mare Nostrum and Sahel Nostrum.

One would also be inclined to take into account the 9 million km2 of the Sahara, given the permeability of the actors and the agendas of the armed terrorist groups (GAT).

Although sparsely populated - 7 million inhabitants - with a very low population density (1 inhabitant/km2 ), the conflict in the Sahel has intrinsically wider regional implications.

Moreover, the interconnection between terrorist groups and major crime, particularly narcotics crime, also leads us to consider the same dynamics and pitfalls for stability in the Sahara as in the Sahel.

- “Polisario's” connection to transnational organised crime

When one delves into the history of the “Polisario”, one sees that the issue of abuse by some members of the movement is not a new phenomenon.

For many years, the “Polisario Front” has been regularly accused of misappropriating humanitarian, financial and material aid provided by NGOs and international organisations.

Many cases of embezzlement have been revealed by the international press. For instance, the Spanish daily El Pais revealed in 1999 that aid worth 64 million pesetas (about 385,000 euros) given by the Spanish Red Cross to the “Polisario” for the purchase of 430 camels to improve the nutritional conditions of Saharawi children had disappeared.

The fact that Algeria has still not allowed the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to visit the Tindouf camps, even if only to carry out a census, does not indicate any positive change in the short term with regard to this proven practice of misappropriation, now openly documented by several international NGOs and UN agencies.

A recent investigation by the European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF) on 26 April 2010 established the co-responsibility of Algeria and the “Polisario Front” in these cases of misappropriation. In addition, the movement is also involved in illegal activities aimed at countering the erosion of popular support. To this end, forced by its crisis of legitimacy among its own troops, the Saharawi movement seems inclined to revert to different types of trafficking and actively participates in illegal immigration networks.

These practices have attracted the attention of the United Nations, which has criticised them in numerous reports. At the same time, many Saharawis linked to the separatist movement have been arrested for acts related to arms trafficking and petrol, cigarette or car components smuggling.

The rise of criminality in the ranks of the “Polisario” must be understood in the context of the impunity that exists in the Sahel and which, in the same way as for terrorism, has favoured the growth of all sorts of illicit trafficking.

The region has become a transit route to Europe for cocaine from Latin America. According to an adviser to the UN Secretary General, Latin American drug traffickers are fighting for control of the trans-Saharan routes that allow them to deliver their drugs to Europe and as far as the Gulf.

- Radical terrorist cells embedded in the Sahel-Saharan strip

The vacuum left by the ideological failure of the “Polisario” has led some of the marginal groups among the younger members of the movement to turn to the radical practice of religion.

It seems that the evolution of the geopolitical context and the end of the Cold War have favoured the replacement of Marxism by radical Islamism which, since September 11, 2001, has emerged as the new transnational ideology challenging the current world order.

My colleague Aymeric Chauprade does not hesitate to affirm that this ideological change of the movement was precipitated by 'the arrival in its ranks of a new generation of militants impregnated with fundamentalism during its passage through Algerian universities'.

The year 2007 was indeed a turning point in the development of terrorism in North Africa. The Algerian Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat (GSPC), created in 1998, decided to integrate itself into the global jihadist movement by becoming, in January 2007, Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM).

This merger with Osama Bin Laden's organisation has favoured the emergence in Algeria of large-scale suicide attacks similar to those carried out by the jihadist movement in Iraq and Afghanistan. This is an unprecedented practice in this country, even during the tragic events of 1990, which plunged Algeria into a "black decade" that bled nearly 100,000 Algerians.

Since 2008, kidnappings of Westerners have been on the rise across the region and have become one of the main expressions of terrorist activity in North Africa.

As published in the Tenerife daily Opinion at the time, the “Polisario Front” alone has carried out 289 terrorist attacks against Spanish citizens, mainly workers in the Phosboucraa phosphate mines in the Sahara and fishermen from the Canary Islands, Galicia, the Basque Country and Andalusia, who worked in the waters of the Saharan coast[2].

- The blockade of Guerguerate reflects the criminalisation of the Algerian policy on the Sahara

The episode of Guerguerate is indicative of the radicalisation or even the criminalisation of the “Polisario’s” strategy. After having observed the greatest restraint in the face of the provocations of the “Polisario”, which had blocked the border crossing of Guerguarate since 21 October 2020, Morocco acted, on 13 November 2020, by a time-bound operation, within the framework of its attributions and international legality, and this, in order to restore free civilian movement in the Guerguerate area.

This decision came only after the good offices of the UN Secretary General and MINURSO had been given all the time they needed. Morocco had, moreover, constantly alerted the Security Council and the UN Secretary General to these multiple violations by the “Polisario”, which had as immediate consequences the destabilisation of the countries of the region.

It should be recalled that to give "substance" to this blockade, the “Polisario” had not hesitated to involve civilians, including women and children, by surrounding them with heavily armed militia elements, indulging in acts of destruction of the road between Morocco and Mauritania and engaging in provocations against the Royal Armed Forces (FAR), whose attitude was one of restraint and patience.

The blockade led to a massive deployment of weapons in the buffer zone, which only the UN could access, under twenty-two tents erected by the “Polisario”, in a flagrant violation of the ceasefire and the Security Council resolutions. The presence of armed “Polisario” elements had been duly noted and documented by MINURSO.

The “Polisario's” provocations are part of an open strategy to challenge the ceasefire that has been in place since September 1991, through explicit calls for war and actions to change the legal and historical status of the area to the east and south of the Moroccan defence.

The Guerguarate passage, which has no military purpose and is open only to civilian and commercial traffic, is vital for the entire West African region. Its blockage is a direct threat to regional peace and security, at a time when the establishment of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) offers, since the first days of 2021, prospects for regional integration, joint development and mutually beneficial cooperation to the countries of North and West Africa and, beyond, Europe.

This is a non-offensive operation without any bellicose intention, following clear rules of engagement that prescribe avoiding any contact with civilians and resorting to the use of weapons only in case of legitimate defence, which aims at securing the flow of goods and persons between Morocco and Mauritania, through the establishment of a security cordon.

This operation, of a rapid and punctual nature with well-defined rules of engagement, led to the fleeing of civilians present on the spot, and the setting on fire of the tents by the armed members of the "Polisario", with the clear objective of destroying the traces of the real intentions behind the blockade, those of destabilisation by the deployment of heavy armaments in the area, and to create the illusion of armed clashes between the Royal Armed Forces and the separatists. No casualties or injuries were recorded during this operation.

By installing a security cordon around the Guerguerate crossing, this operation will prevent the repetition of future provocations by the “Polisario” in the area, which until now has been a lawless zone.

The blocking of the buffer zone and the Guerguerate border post - between 21 October and 13 November 2020 - by the deployment of heavily armed forces was also an act of defiance against the Security Council, which had demanded that the “Polisario” refrain from any act of destabilisation to the east and south of the Moroccan defence apparatus. The UN Secretary General had, moreover, launched three appeals for the preservation of the freedom of civil and commercial movement in the area. In vain!

Morocco has, moreover, firmly supported its efforts with the UN Secretary General, within the framework of the political process, which should resume, before the blockage of Guerguerate, on clear parameters, involving the real parties to the regional dispute and allowing a realistic and feasible solution within the framework of the sovereignty of the Kingdom. It is, moreover, on this basis that France still supports the autonomy plan presented by Morocco in April 2007 and intends to work fully towards Resolution 2548, voted by the UN Security Council on 30 October 2020, opening an inclusive dialogue on the Sahara issue.

- The importance of resolving the regional dispute to ensure stability in the region

The Sahel-Saharan strip is the ideal breeding ground for the persistence of violent extremism and the radicalisation of the most vulnerable populations, both economically and socially.

The instability of this region is not new. Since 2010, Morocco has repeatedly sounded the alarm and warned the international community about the threats, particularly terrorist threats, in this area where crime rhymes with impunity.

Indeed, since the fall of Gaddafi's totalitarian regime in Libya in October 2011 and the offensives carried out by Islamist terrorist groups in 2012 in the southern Sahara, which enabled them to take control of a large part of Mali's territory, separatist impulses are becoming increasingly threatening in this region of the world.

Worse still, all the terrorist organisations have recently taken up residence in this lawless zone, to form new 'partnerships' with non-state armed groups by strengthening their numbers, and to engage in highly lucrative activities (drug and arms trafficking, smuggling) without being worried, But above all, to participate in the destructive project led by transnational terrorist organisations and non-state armed groups, aimed at destabilising the region, which is in any case fragile, in order to ensure a rear base to better coordinate their international actions.

This climate of terror is the result of forced migration by a Sahelian population that lives to the quasi daily rhythm of rackets, executions, bloody attacks and kidnappings.

Without coordinated action, effective and active regional cooperation and an awareness of the need to think about the well-being of the region's population, its future will be jeopardised and in the hands of terrorist organisations.

The idea ardently defended by Algeria of having a micro-state in the region is simply not viable and goes against the current geopolitical context. The former Personal Envoy of the UN Secretary General for the Sahara, Ambassador Peter Van Walsum, had explicitly stated this to the members of the UN Security Council.

The regional dispute over the Sahara is currently experiencing a positive momentum both on the ground and at the UN level. We should capitalise on this momentum and seize this opportunity to resolve this long-standing issue as soon as possible.

The Moroccan autonomy initiative remains the only solution to definitively close this unfortunate chapter. And Algeria could only benefit from such a situation, insofar as it would gain a reliable neighbour, which would allow a Maghrebian reconstruction profitable to all.

- Morocco: a strong player in the fight against terrorism, from the shores of the Mediterranean to the sands of the Sahara

The reality of the Sahara, on the ground, is its emergence as a pole of prosperity, thanks to the New Development Model for the Southern Provinces (NMDPS) carried by Morocco, since 2013, or more recently, the circular and inclusive development models, proposed by Chakib Benmoussa, through the New Development Model (NMD) which allows the local population to realise their right to self-determination on a daily basis, offering them economic opportunities unmatched in the entire region, within a solid framework of local democracy and good governance.

“Polisario”, in the regional chessboard, seems to be surviving only through its willingness to serve Algeria's geostrategic interests. In reality, the “Polisario” only survives thanks to the illegal delegation of authority by Algeria over the Tindouf camps, in flagrant violation of international humanitarian law, especially the Geneva Convention on the Status of Refugees. This is a situation that the Human Rights Committee has highlighted as worrying in its observations on Algeria in 2018.

In the regional dispute over the Moroccan Sahara, two visions seem to oppose each other:

- The first is that of Morocco, which wanted to make the Moroccan Sahara a hub of stability, a link between Europe and sub-Saharan Africa, and an engine of regional growth, through the New Development Model for the Southern Provinces, with a budget of 8 billion dollars. This vision is one of development, democracy and prosperity.

- The second is Algeria's vision. It is a vision based on destabilisation and criminalisation, as demonstrated by the blockade of Guerguerate before the definitive securing of this crossing point on 13 November 2020, and this in clear and repeated violations of the UN Charter.

The international community should rally around the Moroccan vision for the future of the region, and take concrete measures to reach a definitive solution to the regional dispute over the Moroccan Sahara. This includes support for a firm position in favour of the Moroccan Autonomy Initiative as the only basis for a political solution to the regional dispute over the Sahara. This should go hand in hand with a paradigm shift in Algerian diplomacy, so that it can play a positive role in the inclusive political dialogue, to finally put an end to this anachronistic regional dispute over the Sahara.

It would also be appropriate to demand that a census of the populations in the camps and their registration be carried out to reduce the diversion of humanitarian aid.

While Paris intends to develop its military presence by 2023, the 'strategic' neighbourhood of the Sahelo-Saharan countries takes on all its importance. It is in this new diplomatic-military configuration that we must undoubtedly analyse the desire on the part of Algiers to consider the “Polisario Front's” theatre of operations along the Sand Wall as a war zone, both in terms of the media and diplomatically, by drawing a comparison with the Sahel.

By doing so, Algeria seems to confirm its strategy aimed at breaking with the status-quo, born of the cease-fire of September 1991, opening an additional Pandora's box, as it did a decade ago along its common border with Mali.

For its part, Morocco continues to garner more and more support at the international level, as evidenced by the new consulates that have been opened in the Sahara, in addition to the 22 already installed in Dakhla (11) and Laayoune (11). This in itself constitutes important victories for Morocco, whose diplomatic offensive in Latin America and Africa is now decisive.

Therefore, it is undoubtable from the experience acquired in the collection of intelligence - particularly of a human nature - and through the tools of anticipation, of capturing weak signals, of coordinated response of action and of regional, continental, transcontinental and more specifically Euro-Mediterranean cooperation in the field of anti-terrorism, that lies the “recipe” that makes Morocco the strong link in the fight against terrorism between Europe, Africa and the Mediterranean.

Furthermore, the Moroccan model of Islam of the "right middle", based on a serene, and balanced Islam and denouncing religious influences from elsewhere, is also a significant tool in the fight against terrorism.

More precisely, it is a question of recalling the "structuring" reference that constitutes the status of Mohammed VI, as the Cherifian King of Morocco, Commander of the Believers.

Moreover, a strong social resilience, an unfailing determination in the religious domain - via the reinvestment and restructuring of the religious field by the State - also explains this international infatuation for the Moroccan exemplarity.

The Mohamed VI Institute for the training of Mourchidine and Mourchidat Imams is a prominent example. More than 500 Malian and Sahelian Imams have been trained since its creation in 2014 and its inauguration in March 2015.

It is by taking into account the fact that security between the two shores of the Mediterranean is consubstantial with that of the Sahara and the Sahel, that we will succeed in building the broadest possible alliance against the entrenchment of terrorism in North Africa and West Africa.

It is also by considering that this same security in the West African space is not limited to excellent bilateral cooperation, but is built in a broader cooperation, involving both the European Union (EU), the African Union (AU) and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), that resilience will be built against these armed movements, which are now undermining the stability of most of the states in the sub-region.

Let us hope that, after the unanimously welcomed return of Morocco to the African Union in January 2017, Rabat's request in May 2017 to join ECOWAS will become a reality to anchor in time and geography this determined, united and perennial action to fight terrorism.

It is also noteworthy that a motion was transmitted in 2016 by the Gabonese president, Ali Bongo Ondimba, on behalf of 28 AU member states, calling for the suspension of the so-called "SADR" in order to allow it to play a constructive role and contribute positively to the efforts of the UN - which does not recognise the SADR - in the final settlement of the regional dispute of the Sahara.

By Emmanuel Dupuy

[1] El País, “El juez cita como imputado al lider del frente polisario por genocidio”, November 15th, 2016.

[2] Antonio Herrero. El Frente Polisario: una organización con orígenes terroristas. 23 Mai 2021. https://www.cope.es/emisoras/canarias/santa-cruz-de-tenerife/tenerife/noticias/frente-polisario-una-organizacion-con-origenes-terroristas-20210523_1302558